After the coastlines, the mountains are probably the second most distinctive feature of most fantasy worlds. Let's take a look at the development of the Great Caldera's mountains.

|

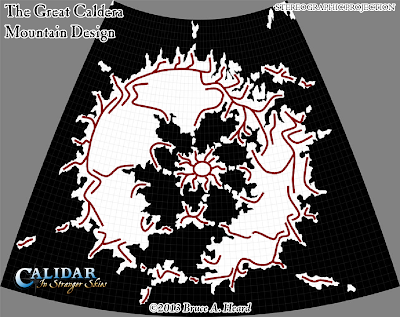

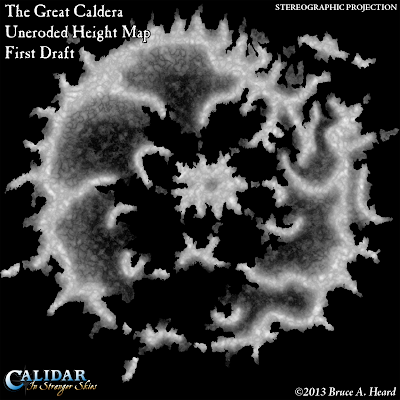

| The Great Caldera Mountain Design, Stereographic Projection |

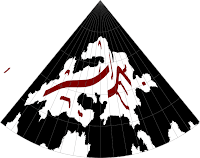

The first image is +Bruce's design for the mountains of the Great Caldera, painted onto the Stereographic Projection from last time. You can see how the mountain ranges generally follow the outside of the circle, forming a gigantic rim around the ancient impact crater. Time has worn it down, and it is broken in a number of places.

Bruce drew these lines as guides for constructing a full height map (also known as a bump map, elevation map, or digital elevation model) of the area. I took the lines, blurred them, messed them up a bit, and converted them into uneroded mountains.

Next, I took the same lines and expanded them out, then messing them up in a similar way to create hills. The second image is the resulting fully-detailed height map.

|

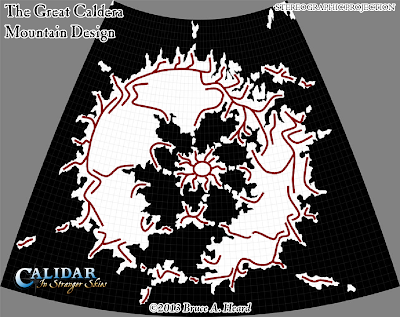

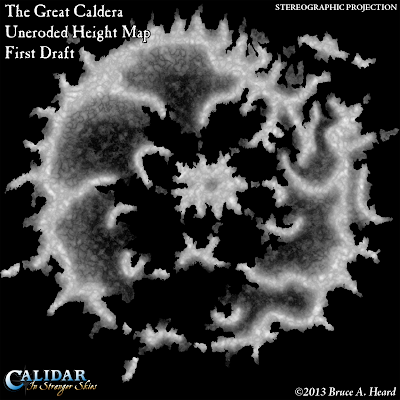

The Great Caldera Uneroded Height Map (First Draft)

Stereographic Projection |

A word about height maps: this map shows elevations, with black being the lowest point – in this case, sea level – and white being the highest. It takes some imagination to understand what's going on, but basically speaking the white points are mountain peaks, while the grey lines in between them are valleys, and the darker grey to almost black areas are hills and plains.

You may be wondering why such a map is necessary or even desirable. The answer is that this map can be loaded into terrain viewer programs, which show it as a 3D model of the terrain. Many computer games use these models to construct their worlds, and just as in those games, it's possible to move around and explore the landscape.Height maps form the basis of all of Calidar's maps, and they open up exciting new possibilities for Calidar's cartography and art. Their altitude data can be used in conjunction with latitude to calculate a simulated climate model, which in turn can even be used to texture the world according to each area's biome. All of this is made possible by the height map, which is why I have spent more than four months so far building, eroding and refining Calidar's geography.

|

The Great Caldera Uneroded Height Map (First Draft - Shaded)

Stereographic Projection |

The third map, on the left, is exactly the same map, but instead of displaying low-to-high elevations as black-to-white, it uses a colour scheme to shade each height, making it a little easier to visualise what exactly is being depicted, but you have to bear in mind that the colours represent height variations, not terrain types.

Blue is sea level, light green-to-darker green is lowlands, light brown-to-dark brown is progressively higher areas, and dark brown-to-white is highlands.

Generally speaking, the lowlands are flatter than higher areas, so it's relatively safe to assume that green areas are lowland plains, or at most rolling hills. But there could also be some lonely mountains in the green areas, too.

Now, you probably noticed that this height map (in both colour palettes) is labelled as being "uneroded". That is to say, it has not undergone simulated erosion to carve mountains and valleys into those mounds. This is a multi-stage process which takes anything from a few hours to a few days, depending on the size of the area and the resolution it needs to be done at. This model is roughly 0.5 km per pixel at full resolution, and the full image is 9,999 x 9,998 pixels. This provides a good level of detail for continental mapping, though perhaps not enough for country-level maps.

The fully eroded version of this map is the Great Caldera map with borders and labels which Bruce revealed in the initial announcement of the +World of Calidar, which you can see below.

|

| The Great Caldera Eroded Height Map (First Draft - Shaded), Stereographic Projection |

Here it is: the first completed draft of the Great Caldera's fully eroded height map. Compare it with yesterday's pre-erosion map, and you can plainly see how the white blobs have been carved into majestic white peaks. What was previously a landscape of blobs has become a proper landscape of plains, hills, mountains and valleys. A lot of land has disappeared during the erosion process, carried down to the lowlands and into the sea by simulated rain and water courses, which is why everything looks so much lower.

Taking a look at the geography of the Great Caldera, at this point it becomes very clear why its borders are located where they are: the political divisions follow natural divisions in the terrain, which split the land of the Caldera into numerous smaller areas.

Note that this is the first draft; there are various problems with this map, and in fact there have been another three passes since this map was completed. I'm quite happy with the fourth draft, so it may well become the final one.

I'm sure many will be impressed with this, but I'm equally sure that some may be thinking: so what? Why is this useful? Why don't you stop talking about things and just show us the finished maps?

Don't worry, we'll get to some major reveals very soon.

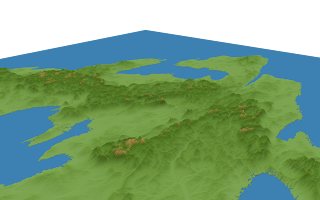

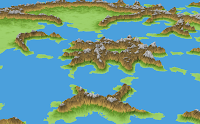

In the meantime, here are some 3D views of the terrain for your enjoyment.

These very simple 3D views of the Great Caldera demonstrate the huge benefit of height maps, which is to say that they are really 3D models. Using these very same height maps, it is possible to generate photorealistic-looking landscape views.

But for now, this is not our goal; the first priority is of course to establish the terrain and its shapes by producing high quality maps of the area. The height maps help in this, too – not only by allowing the correlation of altitude and latitude data for climate shading, but also in generating river maps; in providing shaded relief for political maps; in guiding the creation of hex maps; and other ways besides. I hope you can see why I have chosen to develop Calidar's terrain in this way.

The shading you see here is the same simple, elevation-based shading as on the colour maps above. Note how the flat map's colours have been adopted into the 3D view. It's actually possible to load any image as a texture for the 3D model, so even without photorealistic rendering, you can expect to see more of these 3D views – and prettier ones, too.

More about all of this later. This brings us to the end of our first week of Maps of the Day, exploring the Great Caldera, the heart of the World of Calidar. Thanks for reading! Join us again next week as we preview the shape of the Dread Lands which lie outside the relative safe haven of the Great Caldera.